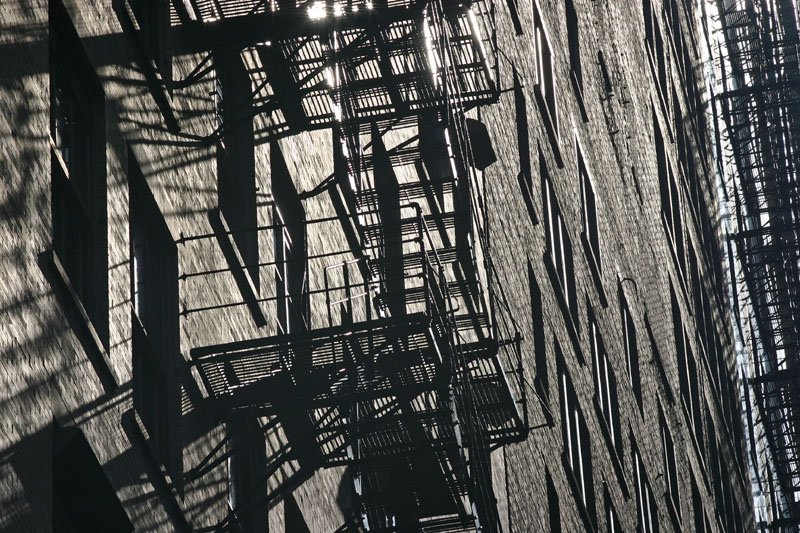

Chicago

Lewis Jordan

mailman farmer fireman

husband father son

…grandson

Born in San Francisco, grew up in Chicago …with the blues (which he too got from time to time)... with learning to associate creative musicians with the advancement of society as we know it.

An international touring and recording musician; poet; actor and playwright. A founding member of United Front, the seminal San Francisco Bay Area ensemble known for its originality, imagination and cultural synthesis. Artistic director of Music at Large.

As a performer Jordan bridges the worlds of music and spoken word—through composition, saxophone and poetry.

San Francisco

In his career, he’s focused on creative structures for improvisation, which has led to his work with artists from a range of disciplines. He has performed with dancers, poets, actors and musicians—including Brenda Wong Aoki, Anthony Braxton, India Cooke, Scott Davis III, Lisle Ellis, Sara Felder, Danny Glover, Ollen Erich Hunt, Mark Izu, Jon Jang, Kash Killion, Genny Lim, devorah major, James Newton, Sandra Poindexter, Q.R. Hand, Donald Robinson, George Sams, Cecil Taylor, pearl ubungen, Richard Wood and others, many presented in his Music at Large series.

His interest continues to be meeting and working with performers delving into their deeper resources for modes of expression which honor their traditions while speaking to the urgency of the present. If that's in B-flat, fine. If it's in time, that could work too. If it's outside, it must be honest.

finding the point

from conscientious objection

to conscious objection

Performing Artist

constructing a just and lasting piece

Years ago, when I first moved to San Francisco, and the Western Addition was getting redeveloped, there was a store at Laguna and Post with a simple sign on its door: There is no end to how much good you can do if you don’t care who gets the credit. I see approaching the stage, or the canvas, with that similar stance towards life. We limit ourselves if we require ourselves to explain how or why each movement, step or sound has to be where it is. There are things we don’t know, maybe don’t need to know, and certainly don’t need to show we know.

...subject is a street musician and drifter. He does not possess any asset potential and accordingly, his case is being placed in a closed status.— Confidential FBI File, October 1978

It’s personal

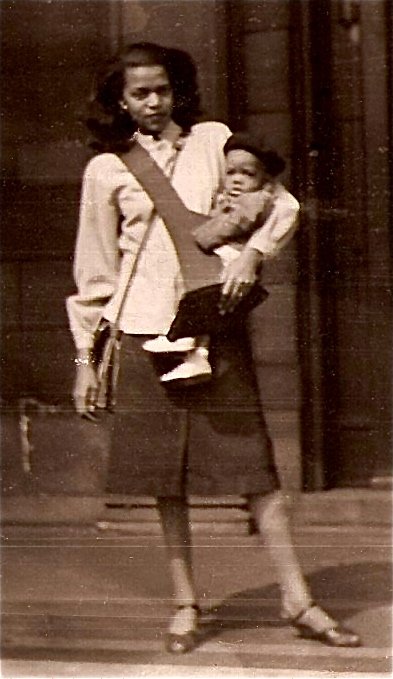

I spent the first year of my life in San Francisco, went with my family back to Chicago, and have come back to spend my adult life in the Bay Area. Aside from the cultural and climate appeal, I moved to San Francisco in the late 1960s to fulfill my service to the country, as a conscientious objector. That would be a service alternative to the military, but, as defined, in the national health, safety or interest. My claim to conscientious objection was grounded in these profound experiences: my visits to my grandfather, my father’s father, who was a Baptist minister in Alabama; the deep spirituality of my mother and father, a spirituality manifest in their respect for the entire world and the peoples in it, rather than through a formal organized religion or rote church-going; and my introduction to Zen Buddhism, which first gave me the ability to fully accept spirituality that was not framed within the Judeo-Christian references of the general society.

Between Chicago and San Francisco, there were four years at St. John’s College, in Annapolis, Maryland. The two important factors were the curriculum at the school and my being away from home. The studies at St. John’s are fashioned around what are called the Great Books of the Western World, the primary texts through which European thought has been expressed and has evolved. From my college preparatory curriculum in high school (including 5 years of math and 3 years of Latin), it was a natural segue to a traditional liberal arts program. In retrospect, though, I have come to see that the Eurocentrism (for lack of a better word) of the curriculum and my being away from home brought a confluence of experience that has parallels in the intellectual class of the colonized which Franz Fanon wrote so passionately about. In other words, there had to be and was for me an awakening to and a learning about my own history that was irrelevant to my college years, and therefore delayed. The tendency would be to evaluate my own history through the lens of the dominating culture’s perspective on that history: that perspective has necessarily been of one self-identified as greater looking at the lesser. Not until I, and like-minded others from many backgrounds, examined myself and other cultures through different lenses was I able to discover the variety and depth that had been un-“discovered.”

For me, the most powerful access to a more inclusive truth about myself, my history, our history, our society as a whole, has turned out to be through music. That began with how strongly I felt the emotional connection with various musicians, in diverse genres and from diverse backgrounds. In that context, my connection with African American musicians—from folk, to blues, to jazz, to avant-garde—was an inspiration to examine my personal history more deeply. Having been academically tracked, there was an education waiting for me that concerned how the passion of art and culture merges or does not merge with our intellectual selves. Beginning with my own instruction in music as a saxophonist, I continue to learn how people have separated art and education for reasons that I have come to understand as maybe pathological. At the least, the reasons are based on conflicting psychological, political and ultimately spiritual views of the world. My own process of understanding how artistic expression is integral to intelligence continues to feed me and has many links.

The improvisation that is so rich in the jazz tradition does not come from the jazz tradition. Rather, it brought about that tradition. That is, improvisation is a natural human approach and response to both the familiar and unfamiliar. It is especially cogent in difficult situations, whether they are of our own making (artistic complexities) or out of our control (natural or manmade emergencies). One of my areas of interest and study is how to understand and appreciate improvisation for its social and cultural potential. It is not just a coincidence that the African American experience has spawned jazz and that improvisation continues to be more easily a part of African Americans’ approach to day-to-day life. Similarly, it is not a coincidence that how we approach life has much to do with how we approach learning. Whether we talk about pedagogy or andragogy, there are attitudes that facilitate learning.

The structure of classrooms, the method of instruction, is clearly not independent of the learning that goes on there. Of particular importance to me is group learning. As we can talk about solo improvisation or group improvisation, we can consider learning as taking place within an individual or within a group. Group learning is a process that still feels like a new pair of shoes to many people, but I think that group learning has to be understood as a major mode of education. Our previous emphasis on individual accomplishment (the first hand raised, the brightest, the most likely to succeed) has helped obscure some important factors relating to knowledge. Among the questions that have traditionally received low priority: Knowledge for whom? When do we learn about each other? How do we learn from one another?

I could put it simply: When I am performing, I am not satisfied if how I and others learn is not part of the agenda. When I am teaching, I am not satisfied if how I and others create is not part of the agenda.

The Spirit Lives

Music is about

first things first

Under Construction

It is a constant struggle to bring into alignment what we do and the reasons we have for what we do. Under Construction refers to acts of solidarity, concrete and otherwise, in the process of giving our future a better present. As a social theme, it calls on internationalism. As an artistic theme, it calls on cultural work. As a personal theme, it requires resonance with emergent conditions. I, you, he, she and they are all works-in-progress. We are constantly required and inspired to build towards, for lack of a better world, a more inclusive society.

Improvisation is a theme in my life and in my work, as a performer and an educator. Although some of us sometimes take the idea of improvisation frivolously and not deeply enough, I find that the spirit of improvisation—and the act does require the spirit—invites me and others to grow and learn.

Lifelong and lifewide learning is

something I believe in, simply because

there’s more going on than we can ever

capture and hold in our hands or in our

minds long enough to completely

know. In other words, we can know

details about specifics in our world,

but the nature of the world itself

and the significance of the details

is in flux.

Venceremos Brigade, 1977, el decimo contingente